Moses is a true Levite (v1). Which tells you, among other things, that he'll be a man of violence (v12! cf Gen 34:25ff; 49:5-7). He is not the Judah-ite King (Gen 49:8-12) to whom the nations will bow. The LORD's Glory will not be united to his company (Gen 49:6).

Moses is not himself the Saviour. His name (v10) means 'saved'. This is not the One Jacob looked for (Gen 49:18) whose name means "salvation" - i.e. Jesus.

But he will share many traits with Him. He will be a priest for the people, acting on their behalf, declaring the word of the LORD. And like a new Noah he will come through waters of judgement (v3 - the 'basket' is simply the same word as 'ark'). And his salvation will mean salvation for all who follow him.

After 400 years of 'radio silence' from God, he leaves his father's company, survives a genocide aimed at eradicating the male seed and is raised by his natural mother in a foreign land. He enters their condition (Acts 7:22) and becomes "great" (lit. v10 and 11). He is set as prince and judge of his people (v14) and this is for their redemption (though they don't see it). But in the Lord's wisdom this redemption won't come through earthly might (v15).

Moses' first 40 years (Acts 7:23) were spent 'becoming great' in Egypt. Imagine it - the greatest empire the world had known. And he was at the centre of it all. He had become wise in all the ways of Egypt and was mighty in word and deed, as Stephen's speech declares. And yet, as Hebrews 11 says:

24 By faith Moses, when he was grown up, refused to be called the son of Pharaoh's daughter, 25 choosing rather to be mistreated with the people of God than to enjoy the fleeting pleasures of sin. 26 He considered the reproach of Christ greater wealth than the treasures of Egypt, for he was looking to the reward. 27 By faith he left Egypt, not being afraid of the anger of the king, for he endured as seeing him who is invisible.

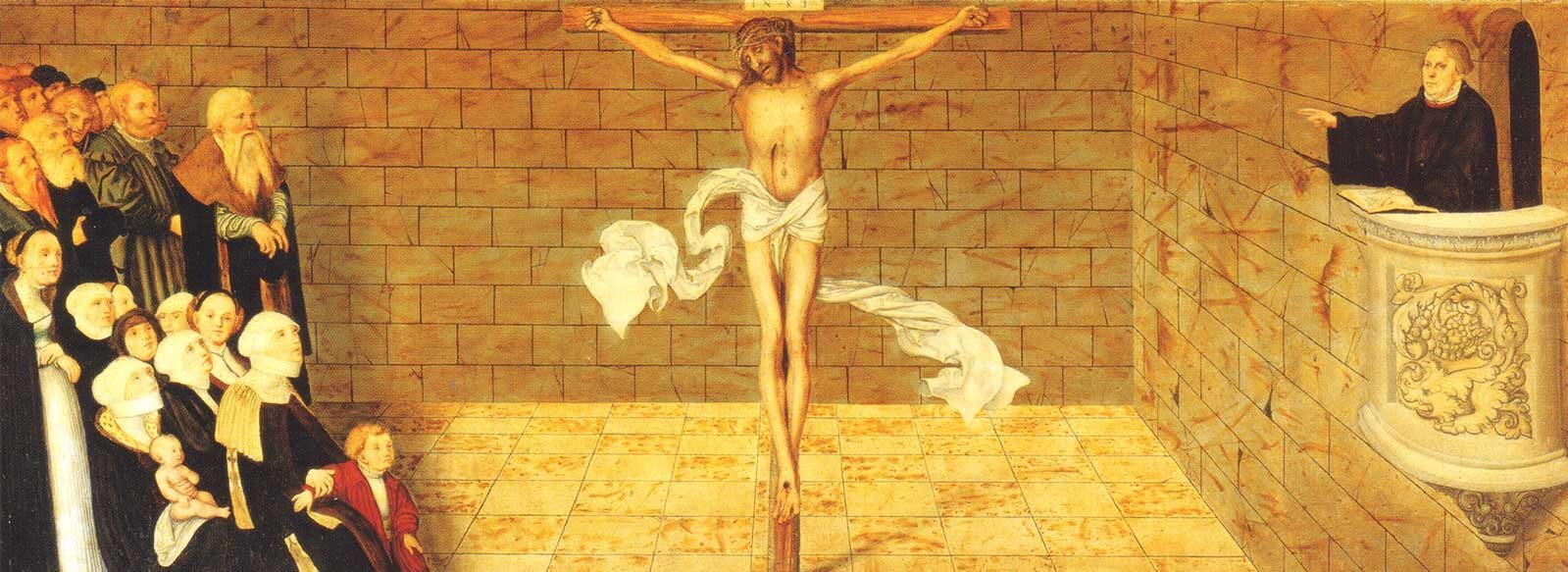

For all its appearance by sight, Egypt offered only 'the fleeting pleasures of sin.' Moses 'saw' something else. Or rather someOne else - the visible Image of the invisible God. And reproach with and for Christ is a greater wealth than all the treasures of Egypt. 'Seeing' and 'considering' this, he refuses his royal identity and sides with his oppressed people for the sake of Christ.

This Levite found a truth that a Benjamite would later describe:

7 But whatever was to my profit I now consider loss for the sake of Christ. 8 What is more, I consider everything a loss compared to the surpassing greatness of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whose sake I have lost all things. I consider them rubbish, that I may gain Christ 9 and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which is through faith in Christ--the righteousness that comes from God and is by faith. 10 I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, 11 and so, somehow, to attain to the resurrection from the dead. (Phil 3:7-12)

Moses too has fellowship with Jesus in suffering. And, as with Paul, it conforms him to Christ's likeness. Moses' second 40 years will be spent becoming a saviour shepherd (v17ff) who waters the flock, defending and winning his bride. This second 40 years was very different to the first. But it's so important.

Redemption will not come through Moses' power politics. He will not 'play the game' and become an inside man in the Egyptian system. And neither will he simply be the insurrectionist bringing redemption through earthly violence. Both forms of worldly power are taken out of the equation.

From v23 the camera focuses in on the Israelite's only hope - not their 'great' man, but their gracious God:

the people of Israel groaned because of their slavery and cried out for help. Their cry for rescue from slavery came up to God. 24 And God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob. 25 God saw the people of Israel - and God knew. (ESV)

God heard. God remembered. God saw. And God knew. What wonderful verbs! Meditate on these today.

And what an awesome Subject for these verbs - repeated every time for emphasis. It is God's action that will bring about redemption. And He is not a callous or indifferent God. The Father Almighty is not deaf, forgetful, blind or ignorant. The cries of His children 'come up' to Him.

We may question His rejection of earthly power and the intollerable wait. But Exodus 2 teaches us something crucial: Though our Father does not redeem according to our wisdom or timing, He does redeem according to His own - according to His own covenant promises and character.

And His response - so typical! - is to send His Angel (chapter 3), the true Saviour and Hero of the Exodus.

More on this tomorrow....

..