A fascinating 40 minute discussion between a philosopher a theoretical physicist and a cosmologist. I even understood some of it!

I can't get the video to embed so click the image or

go here.

Below are some highlights from the discussion. My comments in blue.

David Wallace (philosopher):

If philosophy's learnt anything in two and a half thousand years... it's that you can't start from no-where in trying to understand something. Descartes famously did try to start from nowhere... it was a glorious failure.

Trying to understand things pretty much always presupposes some background set of things that are our starting point. So we can ask all manner of questions about the universe... in asking those questions we are always going to be having certain starting points and presuppositions.

Crucial point

So if we interpret the question in its widest possible sense: 'Why is there something rather than nothing in the widest possible sense? Why is there mathematics, why is there law, why is there logic?" At that level I actually think science can't answer those questions, philosophy can't answer those questions. I actually think those questions aren't answerable. There's nothing to grip onto and so nowhere to start.

But that presupposes naturalism. Aren't you at least curious to employ a presupposition that gives you more answers rather than the naturalistic presupposition that limits the answers?

But if you want to ask more specific questions about why the world that looks anything like this exists, then I think we have learnt a lot. And in a sense what we've seen is a conflict [and a victory] between two very different ways of looking at the world. A way of looking that tries to build everything up from the ground, to explain complicated things in terms of simpler things and to explain more purposeful things in terms of less purposeful things versus an understanding that starts with meaning and purpose as a basic starting point and gets the meaningless and the factual things from it.

The bottom-up approach (empiricism) is attractive because it means we can get our hands dirty by investigating the world. It's satisfying to see complex systems broken down to component parts (but only to a point - taking apart the grandfather clock is fascinating, but the whole is superior to the parts and the story behind it might be even better).

The top-down approach (rationalism) is also attractive because it means that the highest levels of explanation are also the ones with most meaning and purpose. The danger is that it's pure supposition and not grounded in empirical fact.

I think the development of science since the renaissance has almost completely vindicated that first way of thinking about things.

Hang on. For a start you've admitted that the bottom-up approach has rendered us completely unable to answer the question at hand in this debate: Why does the world exist? That's a pretty major short-coming (unless we want to say that everything our empirical net doesn't catch aint fish).

What's more, you've said that presuppositions underlie any understanding of the world. Therefore even the "bottom up" method of empirical enquiry assumes over-arching realities.

Therefore top-down understandings have not been dispatched by the onward march of empirical science. They are unavoidable... BUT ALSO bottom-up enquiries have been extremely fruitful in answering certain questions (with one glaring exception in the question at hand)

So then, how can we hold onto both?

Here's a presupposition that gives us our cake and let's us eat: "The Word who became flesh" There's a Logos to keep the rationalists happy who became a sarkos for the empiricists to investigate. And, hey presto, the unanswerable question gets an answer that is worthy of a universe as gorgeous as ours.

George Ellis (cosmologist, multiverse sceptic):

The "Multiverse" tries to say this universe is incredibly unlikely to be good for life but if you think of all possible universes, they're incredibly unlikely to have life in them, but nevertheless if you have an infinite number of universes then some of them will make it ok and this will give you a scientific explanation... This is a philosophical hypothesis. I can say anything I like about it and it can't be proven true or false. That's the basic observational situation of the multiverse. I think it's a very fine philosophical hypotheses but... it's a faith position. You can believe in the multiverse but you can't prove it.

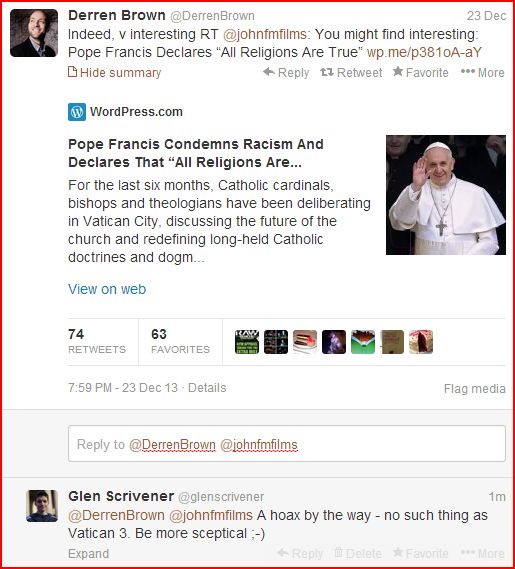

Well said. But fascinatingly, fear of having a faith position is what drives multiverse proponents too...

Laure Mersini-Houghton (theoretical physicist, multiverse proponent): I always get alarm bells when I hear things like 'one universe', 'one creation moment' and 'purpose'... If I were to replace those words with 'divine intervention' or 'God' that would take us 2000 years back to square one.

So both the multiverse sceptic and the multiverse proponent dislike faith positions and that drives them to what they say.

All the while David Wallace points out that we all have presuppositions.

David Wallace: If you want to reason your way to the fact that the world exists you're going to have to make assumptions to that story. You might learn that if you make this very simple assumption or that very simple assumption or these very simple starting points then it will follow that the world exists. That could perfectly well be true. You then have the question of where those starting points arise from... At some point you're going to have to stop explaining. And that's not a matter that science won't be able to explain... it would be a matter that we wouldn't have any resources to explain.

...Your explanation [of anything] is always going to have a thing that you're presupposing to do the explaining.

Ok, what about a presupposition that manages to bridge the top-down and the bottom-up positions. One that accounts not only for a life-sustaining universe, but for the kind of life that we call life. What about an explanation for life that actually LOOKS like what we call life: loving, joyful, personal, self-giving life-in-relationship kinda life.

Maybe we should go back 2000 years and investigate the Word become flesh. We might find that going back is the way forward.